Falling Back in Time with Union Station

This week, we take a look at a building whose known usefulness tends to eclipse its lesser-known beauty. Located just west of the Loop, and taking up about a 9-city-block area (much of that being underground construction), Union Station is the last of the great train stations that used to dot Chicago’s downtown landscape. Finished in 1925 after an arduous 12-year construction period, it was designed by the famous Daniel Burnham — though unfortunately completed only after his death. Burnham was part of the prolific architectural firm of Graham, Anderson, Probst & White (originally Graham, Burnham & Co.), the company responsible for many of Chicago’s most famous buildings. From Beaux-Arts to Chicago School Style to Art Deco, they grew and changed with trending architectural styles and philosophies, and gave us such familiar and beloved buildings as the Merchandise Mart, the Shedd Aquarium, and the Wrigley Building.

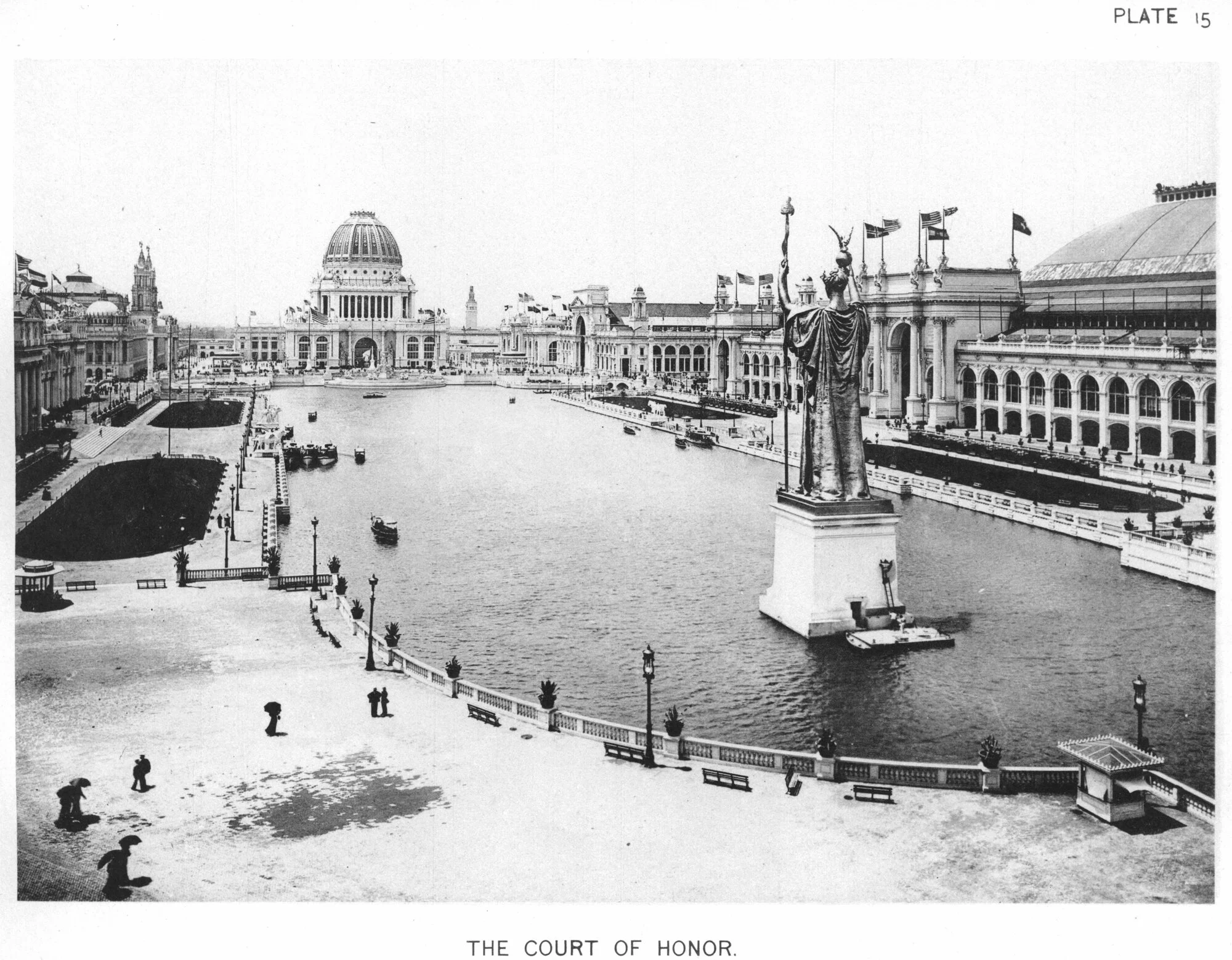

But Daniel Burnham was so much more than an architect. A protégé of the “Father of the Skyscraper” himself, William LeBaron Jenney, Burnham famously said, “Make no small plans: they have no magic to stir men’s blood” — and so it follows that he had two incredibly influential roles in Chicago’s development. He was the main designer in the 1909 Plan of Chicago, a plan in which he envisioned the quickly developing city as becoming a “Paris on the Prairie”: French-inspired details (e.g., Buckingham Fountain), Beaux-Arts architecture, green spaces within walking distance of every citizen in the city, and grand boulevards radiating out from an orderly and mighty civic center. Over a decade before that, though, he served as director of the World’s Fair of 1893 (aka, the World’s Columbian Exposition), a position which afforded him the opportunity to show the world (and especially the U.S.) what his ideal city would look like. Over the course of the Fair’s brief 6-month duration, he gave its 25 million international visitors an awe-inspiring, grand welcome by way of his acclaimed “White City.” The White City, a stunning collection of Beaux-Arts buildings awash in gleaming white, represented Burnham’s ideal city: taking its cues from ancient Greece and Rome, and from French Neoclassicism, the White City communicated in one glance Burnham’s desire for a beauty and order that would lift people to a higher civic standard. Architecture, he felt, could elevate human beings through its beauty; indeed, it could restore a sense of order and culture to what Rudyard Kipling famously called, “a real city” — and one which he “urgently desire[d] never to see again. It is inhabited by savages.” Burnham’s desire was to essentially train and elevate the masses through architecture; it is, in fact, largely from his White City that the “City Beautiful Movement” sprung, influencing many American cities’ design.

But I digress: I bring up the World’s Fair to set the stage for getting inside the mind of Daniel Burnham, a proper context for exploring Union Station. Indeed, entering Union Station’s Great Hall by way of its marble staircases gives one the impression of truly going inside something special — in this case, Burnham’s imagination. One descends the stairs and goes from relative shadow to the open, lofty space of the Great Hall: an amazing vaulted skylight — recently restored — allows endless natural light into the space, while the open floor plan gives one the sense of endless, air-filled space. One of the main tenets of Burnham’s design philosophy–and indeed a cornerstone of the Chicago School Style–is the prioritizing of “light and air” in a building’s design. Hence a light court in so many turn-of-the-century Chicago buildings: offices could be deep inside a building, but still have natural light; air could flow freely through a court’s windows and freshen a building before air-conditioning. A “Chicago Window” is the embodiment of this “light and air” philosophy: a fixed middle pane to allow maximum light, two movable side sashes to allow maximum air.

But I digress again: it is difficult to stay on topic with a subject as large and influential as Daniel Burnham! Long story short, Union Station is like the beating heart of Burnham’s Chicago: it is grand, orderly, massive, awe-inspiring; it is filled with light, space, and life. Inspiring in a much different way than more modern, minimalistic constructions, Union Station captures the essence of the Beaux-Arts style, with its elegant Neoclassical details and proportions, and transports one to Burnham’s beloved inspiration, Paris — even if just for a brief moment, as one rushes to catch a train.

Daniel Burnham’s final resting place on his own island at Graceland Cemetery, Chicago