A Home for Creative Expression: The Fine Arts Building

If you’ve been to the area around the famous Art Institute of Chicago, Grant Park, and Millennium Park – popular spots not only for tourists, but also for Chicagoans depending on what event is being offered there – chances are you’ve walked by this building without even a glance. This is truly one of my favorite buildings in Chicago for a number of reasons, one of which is its relative obscurity in the middle of this very well-traveled part of Chicago. I like to root for the lesser-known, the second fiddle, the underdog. And the Fine Arts Building, though rather impressively tall at 8 stories when it was built in 1885 (with later floors added), seems to be squeezed in on the incredibly impressive Michigan Avenue Cliff – that “cliff” of fantastic architecture from the 1880s through the 21st century, much of it dating from the turn of the century.

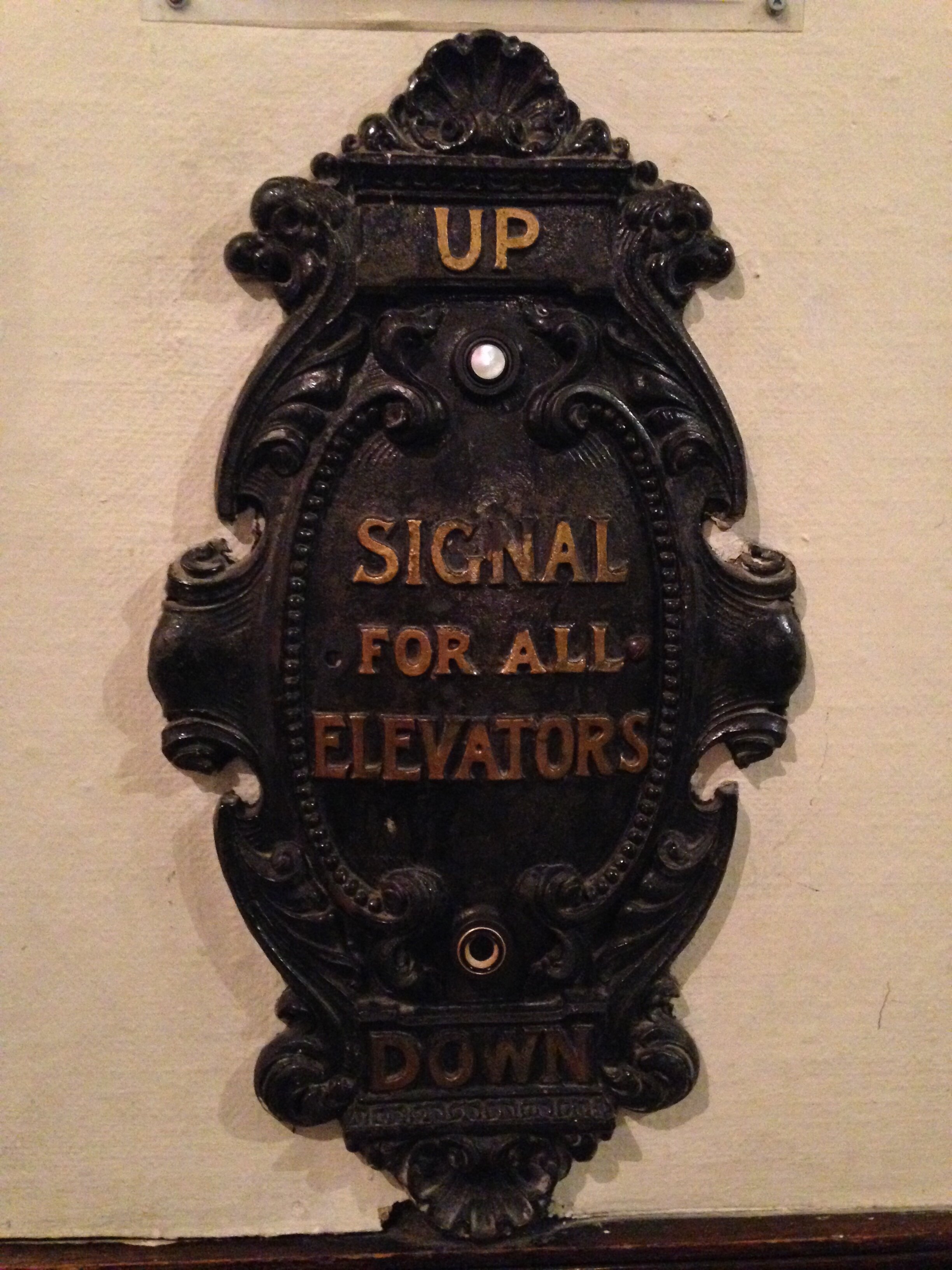

I recommend this building to guests who are looking to find hidden gems – not super niche or esoteric spots, but rather truly historically and architecturally rich spots like this that are enjoyable for most people, whatever their interests may be. This building, for starters, has the only elevators left in the city that are still operated by human beings who ride along with you. (One of them – a stout, handsome Polish man who’s been there for years – thankfully humors me when I feel like using the handful of Polish words and phrases that I know.) Here, I often find myself telling tour guests about the advent of elevators, and how important the invention was to creating taller buildings. The name we associate with elevators – Elisha Otis – didn’t really invent the elevator, per se. The idea of a platform that would actually carry people from one floor to another – what they called a “flying chair” – was introduced by King Louis XV himself for his palace in Versailles so that he could easily access his mistresses’ lodgings. But despite advancements in elevating technologies, safety was always an issue. Enter Elisha Otis, a Vermont inventor who simply wanted to figure out an efficient way to clear a factory floor of debris. Otis debuted what would become the watershed invention in elevator history: the safety elevator, which would automatically stop if the hoisting cables broke, and he bravely debuted his invention at the New York City World’s Fair in 1853.

(An interesting side note about the relative value we place on space and height: isn’t it interesting that nowadays – and since the invention of skyscrapers and safety elevators in general – we value the top floors of a building as exclusive spaces meant for successful and/or wealthy people? Think of penthouses; think of high-up offices with a view. Yet before the invention of the safety elevator, such an exclusive space would have been closer to ground level, for the truly wealthy and successful shouldn’t have to contend with flights of stairs to get to their office or home. Let the poor and working class have the misfortune to have to ascend the stairs instead.)

The Fine Arts Building was built between 1885 and 1887 as the “Studebaker Brothers Lake Front Carriage Repository,” a Midwestern headquarters for the company that would eventually build cars, but which at the time produced 75,000 carriages annually. Its first “horseless carriage” was electric, and introduced in 1902; in 1904 it launched gasoline-powered engines. The giant plate glass windows in the base of the Fine Arts Building were intended to maximize window-shopping potential for wealthy passers-by. Imagine the likes of “Gone with the Wind” carriages displayed in those windows! Indeed, to this day, there remains an overlooked nod to the building’s original purpose: you can actually see “STUDEBAKER” carved into the pink granite in the middle of the building, just above ground level.

By the mid-1890s, the Studebaker Brothers decided to create a bigger, better headquarters a bit south on Wabash, and a society friend of theirs, Charles C. Curtiss – an established music publisher – gave the necessary push for converting the building into what it is to this day: a collection of the best minds in music, architecture, painting, and any other art you can think of. Frank Lloyd Wright had a studio here, as did famous American sculptor Loredo Taft and W.W. Denslow, the illustrator of the original Wizard of Oz. Today, you can find such interesting artisans and shops as William Harris Lee & Co. (a stringed instrument repair shop), Performers Music (a rare sheet music store with gorgeous wood and leaded glass doors), and the American Rhythm Center (a diverse dance studio).

The L.H. Selman Glass Paperweight Gallery is eye-opening and absolutely stunning: I even splurged and bought a $100 paperweight for my birthday a few years ago, I was so entranced learning about the history of the art. I’ve had the good fortune to be able to play an actual old Stradivarius violin at one of the rare violin shops; I’ve heard opera circling up the open stairs. I have yet to find this building completely silent, and that’s one of my favorite things about it: it lives. No matter what day or time you explore this building, you can always hear human creativity happening – you might even catch the CYSO (Chicago Youth Symphony Orchestra) practicing.

L.H. Selman Gallery — I love it!

There’s so much I love about this building – from the unique elevators, to the detailed woodwork, to the variety of creative expression happening down every hall. And you’re not meant to simply appreciate it from outside: this is a building that invites us – its audience – to actively engage with its tenants every 2nd Friday of the month in an event they call “Open Studios.” Imagine a leisurely evening stroll around the building, floor by floor, dazzled by a singer here, a painter there, surrounded by fellow human beings who simply love the arts. The experience lifts the soul.

When you visit this wonderful hidden gem, simply wait for the elevator at ground level, and then ask to be taken to the top. You’ll exit the elevator at the stunning top floor, surrounded by turn-of-the-century murals you can’t see anywhere else. Then, walk your way down floor by floor, and simply enjoy this space that throws you back in time, yet remains current and very much alive to this day.